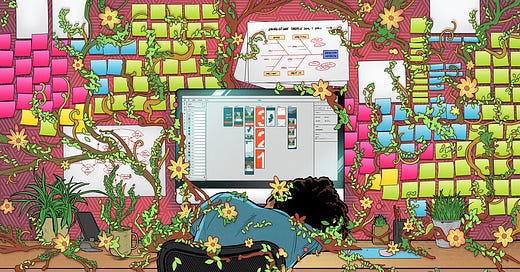

Illustration by Matthew Warlick

“Hey, we need to grab some things from the car. Come join us.”

I was feeling pretty good about myself when my company’s chief executive officer and VP of Design asked me to join them for a quick walk to the rental car. We had just called a half-hour break in our day-long stakeholder sessions, which, despite subbing me in as facilitator at the last minute, were going reasonably well, from what I could tell. Several of us from our agency were onsite at the client’s headquarters to interview several top-level executives in succession over the course of two very long days.

As the CEO, the VP, and I made the trek down the corridor and out to the car, I was excited to receive whatever feedback they had on how I’d run the meetings so far. I was so certain that this was the conversation we were about to have that I didn’t even register the words the CEO said at that moment for a good five, felt-like-forever seconds.

“We need you to lay off Dylan,” he said.

“I don’t follow. Lay off him how?” I said, baffled now.

The CEO elaborated, “You were giving Dylan death stares in there, and we think the client noticed. So we want you to back off of him.”

I quickly replayed the last couple of hours, trying to figure out what he meant, when it dawned on me. “Oh! You mean when he kept whispering to me during the interview and showing me his doodles? He was breaking my concentration while I was trying to focus, so yeah, I may have given him an exasperated look, but nothing beyond that.”

You might think I was speaking of a toddler instead of our very much adult creative director, who, up until two days prior, had been solely responsible for conducting these interviews. That was when the VP decided he wasn’t up to it and gave the responsibility to me, the only experienced researcher on the team. Dylan, though an exceptionally talented designer and an all-around great human, had little research experience and was, at the time, entirely in over his head in professional situations. Our VP knew that from the start, but he still wanted Dylan to lead the client interviews… until he didn’t. So instead of having weeks to prepare for these meetings, I had a day to revise someone else’s questions and create my own approach.

Without proper prep time, success would depend on my ability to stay present and responsive in the conversations so I could direct them where they needed to go. Instead, Dylan was to my right, nervously making jokes, asking inappropriate follow-ups, and pulling my focus to look at his sketchnotes. And yet, what mattered most to my CEO and VP was the fleeting “look” I gave Dylan in response, who, though taken off this very task for valid reasons, apparently needed their protection from me and my evil “death glare.”

I waited for them to get to how they thought the interviews were going. But that part of the conversation never came. No bread on this feedback sandwich. Nothing from them about my efforts — not then or after we wrapped. I processed my feelings about being scolded enough to return to the session despite feeling derailed.

What I was certain I could not do in that moment was react. As any black woman in a professional setting can tell you, it is understood that the bar for the amount of emotion we can show before being judged is so low that it may as well be on the floor. We are often told our tone or demeanor is somehow antagonistic or that we’re being difficult for just reacting to a given situation as anyone would.

Ultimately everything went fine — for the client and our project. But for me, familiar feelings of isolation took hold. It could not have been clearer that “appearances” in front of the client and Dylan’s unconfirmed feelings were of higher priority than supporting me, the competent person doing the primary job that day. The one who should have had the assignment from the start.

So why share this story? I mean, this wouldn’t even make the top ten on the list of demoralizing work-related things that have happened to me. But it’s a perfect example of the types of interactions that lead to career “death by a thousand cuts” that so many of us must endure. On its own, the incident wasn’t a big deal. But in context- the stress of taking over the tasks at the last minute, making travel plans, arranging for care for my ill senior dog, all so I could show up to try my best, but end up feeling like shit — it was demoralizing. And it was only one of several encounters with leadership that resulted in notes on my performance evaluation about how I needed to improve how I “interact with others.”

The reality is that no matter how objectively good our work is, perception of it is always filtered through whatever biases company leadership or one’s immediate management holds. What makes this exchange stand out most for me is how completely unnecessary it was. No one else in that room cared about a brief look on my face, and to this day, I don’t believe the CEO actually did either. This was a power play. A way to put me off-kilter and keep me in check. Letting me know where I stood was more important than the quality of my work.

It wasn’t like I was working for some giant, soulless behemoth of an enterprise. It was a small product development agency that explicitly stated that one of its company values was to have each other’s back. It was a “think of us as family” type of company. Though I know I should never have been taken in by it, the illusion initially felt comforting to someone like me, someone who didn’t have much family of my own.

My entire two-plus decades-long career is punctuated with stories just like this.

And I’m just… really fucking tired of all of it.

“The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.”

― Maya Angelou

For much of the time I’ve been designing for tech, I thought my dissatisfaction stemmed from my needing too much from my job because maybe my life was somehow imbalanced. But looking back on those expectations — needing an environment of mutual respect, desiring collaboration, wanting to establish good processes, encouraging focus on outcomes, expecting the work to be more about execution than planning — I see now it wasn’t a “me” problem, but just the usual corporate gaslighting. And whenever I initiate public discussions about design work satisfaction, I find these feelings are pretty universal — the more you care, the more disappointed you are. Not disappointed with the actual functional duties of the job but with the neverending compromises and tenuous respect the role commands.

I wasn’t entirely convinced that the issue was as widespread as it seemed until a few months ago when I asked this question on Twitter:

When I posed the question, I was definitely not prepared for the response it would generate. Story after story in the replies and my direct messages full of recurring themes of pain and disappointment from dedicated folks who just wanted to do the work.

When we talk about the challenges of this industry, what often gets lost in all the noise is that most of us got into it to make a positive impact. But when we see time and time again that the only obstacles to achieving that are just these stupid, fixable things that leadership refuses to prioritize, it has a corrosive effect on how we feel about our careers.

This reply to that thread from Karen VanHouten sums it up nicely:

“I have a hard time articulating it, but for me, the most consistent and hardest thing is this: it feels like there is a huge contradiction between the outcomes we are told we are being hired to deliver and the outcomes we are actually expected to deliver on the job.”

While none of this is exclusive to the UX field, it does feel more hypocritical that we continue to remain so fraught by these issues, given our mandate of being “human-centered.” I mentally clock all of the blogs, talks, and podcasts about inclusive design and equity, only to later see those same people announce “A bit of personal news” on LinkedIn that they’re joining the very corporations causing the most harm because they’ve convinced themselves that they’re going to help “change them from the inside” when in reality it’s because times are hard and those jobs hold the most prestige and offer the highest pay.

But you know, at some point, we’re all going to have to own our choices and be really honest about their impacts. With the seemingly endless layoffs of late, this is as good a time as any to have the hard conversations we’ve been avoiding about how little of what we actually get to do provides any value — to anyone.

Think about how often you see the “this is me giving a talk at a conference” photo on a designer’s social media profile vs. “this is me doing my job with/for other people.” Before you get riled, I am not saying there’s anything wrong with this. However, the reason the former is considered the more desirable image to project ties directly to the higher value we place on individualistic success in this industry.

In my not-entirely-humble opinion, design is first and foremost about realizing ideas, both large and small — trying, failing, trying again, and putting concepts through their paces, all while considering the various ways they won’t meet the needs of many who will come to depend on them — then doing what we can to address those gaps. It’s a continuous process full of messy details that matter, details that give us reasons to wake up ready to roll up our sleeves and dig in. Every time we get distracted from this by nice slide decks or elevate individuals to well-known status for talking about design instead of focusing on the integral parts of how and why we create solutions, we move the industry further away from its purpose.

It kills me how much we’re stuck in this constant loop of repackaging and reformalizing frameworks and methods that have been around in some form the entire time while ignoring the numerous ways they aren’t working but never fully addressing the fundamental reasons doing this work well is nearly impossible. As you can see from that thread linked above, designers aren’t trying to leave the profession. They want to leave all the other bullshit; lousy leadership, dysfunctional organizations, working without support and being constantly blocked from trying to achieve better outcomes.

So here I am, with over two decades in design, half of that in UX-y type roles specifically, turning in my Post-its. I can’t continue to live in reaction mode to all the inequity, bias, and dysfunction. Your girl is tapped out. I need to be doing work where thinking critically and drawing inspiration from the world around me is a normal and expected part of the creative process, not an act of rebellion against some marginally effective framework someone made up to look smart.

I’m returning to the media production roots of my early career. A time when I made things I was proud of, but this time armed with a ton of life lessons and the freedom to realize my own vision. I’m excited to build a company whose mission will be, in large part, dedicated to contributing resources to help designers learn and look at the world they design for (and against) more critically and expansively.

“By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: ‘Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality. ‘”

― bell hooks

If you haven’t already, I invite you to follow the journey by subscribing to this blog, where I will announce upcoming projects and send invites to a new online community.

Oh, about that title… I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to give a nod to the late great Douglas Adams, who inspired others to lead with humor and humility. His amazing books got me through some of the most challenging times of my life. He also taught me the proper way to fly:

“The Guide says there is an art to flying,” said Ford, “or rather a knack. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss.”

― Douglas Adams, Life, the Universe and Everything

Here’s to missing the ground for as long as we can. Keep flying.